C++ 虛擬函式表

C++類別在記憶體中的儲存方式

C++ 記憶體分為 5 個區域:

- 堆 heap :由 new 分配的記憶體塊,其釋放編譯器不去管,由程式設計師自己控制。如果程式設計師沒有釋放掉,在程式結束時系統會自動回收。涉及的問題:「緩衝區溢位」、「記憶體洩露」。

- 棧 stack :是那些編譯器在需要時分配,在不需要時自動清除的儲存區。存放區域性變數、函數引數。存放在棧中的資料只在當前函數及下一層函數中有效,一旦函數返回了,這些資料也就自動釋放了。

- 全域性/靜態儲存區 (.bss段和.data段) :全域性和靜態變數被分配到同一塊記憶體中。在 C 語言中,未初始化的放在.bss段中,初始化的放在.data段中;在 C++ 裡則不區分了。

- 常數儲存區 (.rodata段) :存放常數,不允許修改(通過非正當手段也可以修改)。

- 程式碼區 (.text段) :存放程式碼(如函數),不允許修改(類似常數儲存區),但可以執行(不同於常數儲存區)。

注意:靜態區域性變數也儲存在全域性/靜態儲存區,作用域為定義它的函數或語句塊,生命週期與程式一致。

其中物件資料中儲存非靜態成員變數、虛擬函式表指標以及虛基礎類別表指標(如果繼承多個)。這裡就有一個問題,既然物件裡不儲存類的成員函數的指標,那類的物件是怎麼呼叫公用函數程式碼的呢?物件對公用函數程式碼的呼叫是在編譯階段就已經決定了的,例如有類物件a,成員函數為show(),如果有程式碼a.show(),那麼在編譯階段會解釋為 類名::show(&a)。會給show()傳一個物件的指標,即this指標。

從上面的this指標可以說明一個問題:靜態成員函數和非靜態成員函數都是在類的定義時放在記憶體的程式碼區的,但是類為什麼只能直接呼叫靜態成員函數,而非靜態成員函數(即使函數沒有引數)只有類物件能夠呼叫的問題?原因是類的非靜態成員函數其實都內含了一個指向類物件的指標型引數(即this指標),因而只有類物件才能呼叫(此時this指標有實值)。

虛擬函式表

C++中虛擬函式是通過一張虛擬函式表(Virtual Table)來實現的,在這個表中,主要是一個類的虛擬函式表的地址表;這張表解決了繼承、覆蓋的問題。在有虛擬函式的類的範例中這個表被分配在了這個範例的記憶體中,所以當我們用父類別的指標來操作一個子類的時候,這張虛擬函式表就像一張地圖一樣指明瞭實際所應該呼叫的函數。

C++編譯器是保證虛擬函式表的指標存在於物件範例中最前面的位置(是為了保證取到虛擬函式表的最高的效能),這樣我們就能通過已經範例化的物件的地址得到這張虛擬函式表,再遍歷其中的函數指標,並呼叫相應的函數。

C++物件的記憶體佈局(x86環境)

只有資料成員的物件

#include<iostream>

class Base1 {

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

};

int main() {

std::cout << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

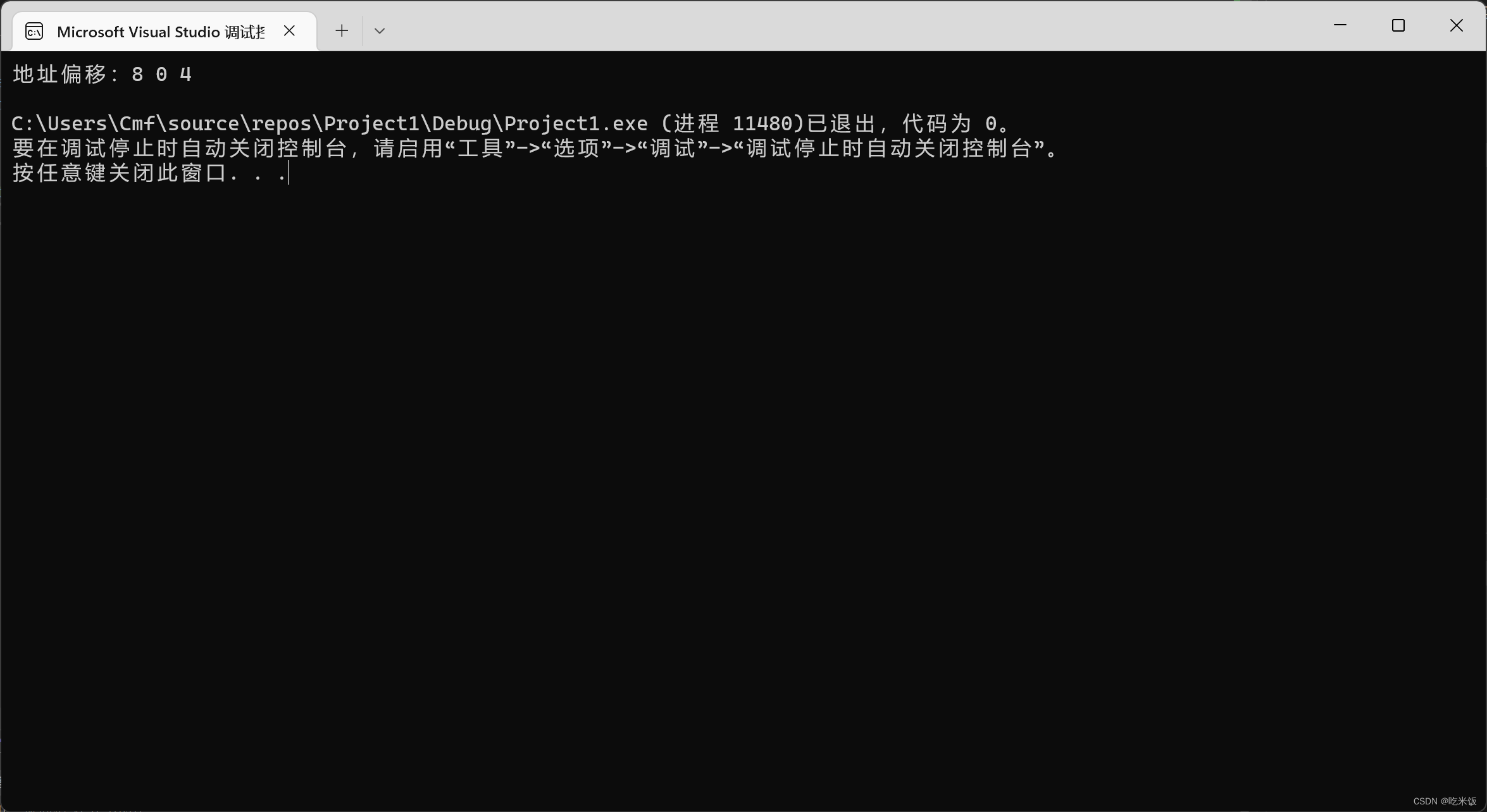

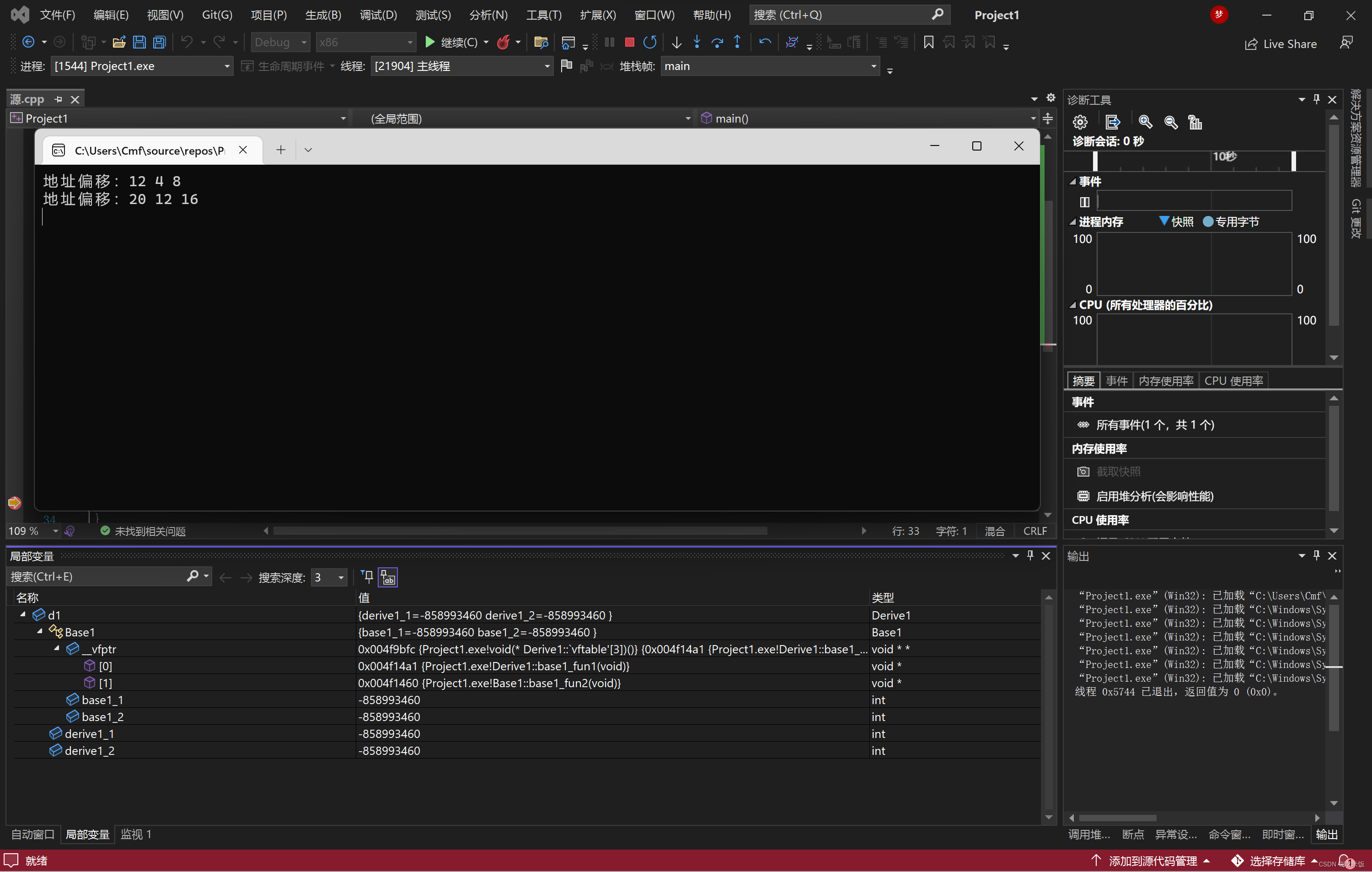

執行結果

可以看到,成員變數是按照定義的順序來儲存的,最先宣告的在最上邊,然後依次儲存!類物件的大小就是所有成員變數大小之和(嚴格說是成員變數記憶體對齊之後的大小之和)。

擁有僅一個虛擬函式的類物件

#include<iostream>

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

Base1 b1;

return 0;

}

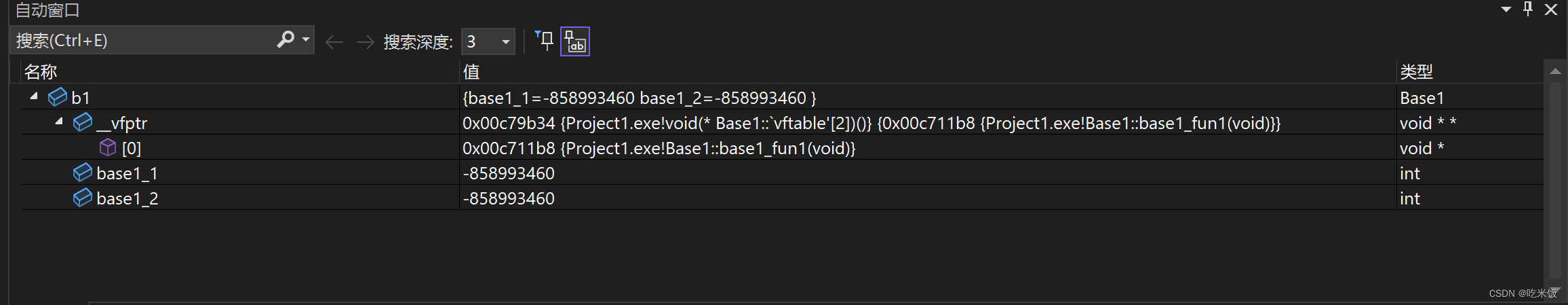

執行結果:

多了4個位元組?且 base1_1 和 base1_2 的偏移都各自向後多了4個位元組!說明類物件的最前面被多加了4個位元組的東西。

現在, 我們通過VS2022來瞧瞧類Base1的變數b1的記憶體佈局情況:虛擬函式指標_vfptr位於所有的成員變數之前定義。

- 由於我沒有寫建構函式,所以變數的資料沒有根據,但虛擬函式是編譯器為我們構造的,資料正確!

- Debug模式下,未初始化的變數值為0xCCCCCCCC,即:-858983460。

base1_1 前面多了一個變數 _vfptr (常說的虛擬函式表 vtable 指標),其型別為void**,這說明它是一個void*指標(注意不是陣列)。

再看看[0]元素, 其型別為void*,其值為 ConsoleApplication2.exe!Base1::base1_fun1(void),這是什麼意思呢?如果對 WinDbg 比較熟悉,那麼應該知道這是一種慣用表示手法,她就是指 Base1::base1_fun1() 函數的地址。

可得,__vfptr的定義虛擬碼大概如下:

void* __fun[1] = { &Base1::base1_fun1 };

const void** __vfptr = &__fun[0];

大家有沒有留意這個__vfptr?為什麼它被定義成一個 指向指標陣列的指標,而不是直接定義成一個 指標陣列呢?我為什麼要提這樣一個問題?因為如果僅是一個指標的情況,您就無法輕易地修改那個陣列裡面的內容,因為她並不屬於類物件的一部分。屬於類物件的, 僅是一個指向虛擬函式表的一個指標_vfptr而已,注意到_vfptr前面的const修飾,她修飾的是那個虛擬函式表, 而不是__vfptr。

我們來用程式碼呼叫一下:

/**

* x86

*/

#include<iostream>

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

virtual void base1_fun1() {

std::cout << "Base1::base1_fun1" << std::endl;

}

virtual void base1_fun2() {

std::cout << "Base1::base1_fun2" << std::endl;

}

};

/*

對(int*)*(int*)(&b)可以這樣理解,(int*)(&b)就是物件b的地址,只不過被強制轉換成了int*了,如果直接呼叫*(int*)(&b)則是指向物件b地址所指向的資料,但是此處是個虛擬函式表呀,所以指不過去,必須通過(int*)將其轉換成函數指標來進行指向就不一樣了,它的指向就變成了物件b中第一個函數的地址,所以(int*)*(int*)(&b)就是獨享b中第一個函數的地址;

又因為pFun是由Fun這個函數宣告的函數指標,所以相當於是Fun的實體,必須再將這個地址轉換成pFun認識的,即加上(Fun)*進行強制轉換:簡要概括就是從b地址開始

讀取四個位元組的內容,然後將這個內容解釋成一個記憶體地址,然後存取這個地址,然後將這個地址中存放的值再解釋成一個函數的地址.

*/

typedef void(*Fn)(void);

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

Base1 b1;

Fn fn = nullptr;

std::cout << "虛擬函式表的地址為:" << (int*)(&b1) << std::endl;

std::cout << "虛擬函式表的第一個函數地址為:" << (int*)*(int*)(&b1) << std::endl;

fn = (Fn) * ((int*)*(int*)(&b1) + 0);

fn();

fn = (Fn) * ((int*)*(int*)(&b1) + 1);

fn();

return 0;

}

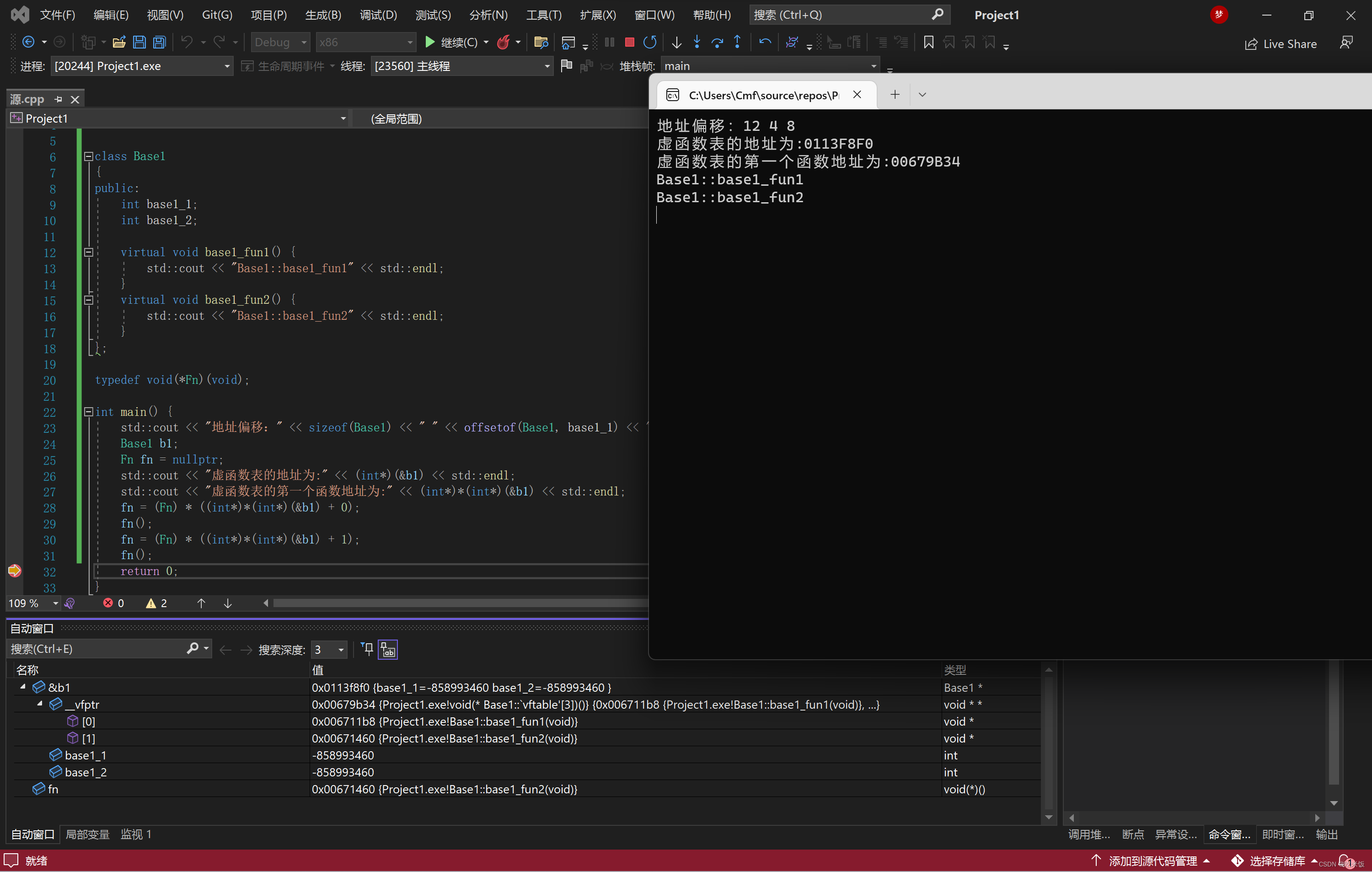

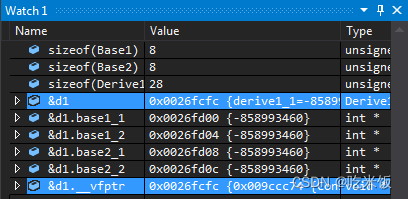

擁有多個虛擬函式的類物件

在上個程式碼呼叫虛擬函式的日子中你有沒有注意到,多了一個虛擬函式, 類物件大小卻依然是12個位元組!

再看看VS形象的表現,_vfptr所指向的函數指標陣列中出現了第2個元素,其值為Base1類的第2個虛擬函式base1_fun2()的函數地址。

現在, 虛擬函式指標以及虛擬函式表的偽定義大概如下:

void* __fun[] = { &Base1::base1_fun1, &Base1::base1_fun2 };

const void** __vfptr = __fun[0];

通過上面圖表, 我們可以得到如下結論:

- 更加肯定前面我們所描述的: __vfptr只是一個指標, 她指向一個函數指標陣列(即: 虛擬函式表)

- 增加一個虛擬函式, 只是簡單地向該類對應的虛擬函式表中增加一項而已, 並不會影響到類物件的大小以及佈局情況

前面已經提到過: __vfptr只是一個指標,她指向一個陣列,並且:這個陣列沒有包含到類定義內部,那麼她們之間是怎樣一個關係呢?

不妨,我們再定義一個類的變數b2,現在再來看看__vfptr的指向:

通過視窗我們看到:

- b1和b2是類的兩個變數,理所當然,她們的地址是不同的(見 &b1 和 &b2)

雖然b1和b2是類的兩個變數, 但是她們的__vfptr的指向卻是同一個虛擬函式表

由此我們可以總結出:同一個類的不同範例共用同一份虛擬函式表, 她們都通過一個所謂的虛擬函式表指標__vfptr(定義為void**型別)指向該虛擬函式表。

那麼問題就來了! 這個虛擬函式表儲存在哪裡呢?

- 虛擬函式表是全域性共用的元素,即全域性僅有一個.

- 虛擬函式表類似一個陣列,類物件中儲存vptr指標,指向虛擬函式表。即虛擬函式表不是函數,不是程式程式碼,不肯能儲存在程式碼段。

- 虛擬函式表儲存虛擬函式的地址,即虛擬函式表的元素是指向類成員函數的指標,而類中虛擬函式的個數在編譯時期可以確定,即虛擬函式表的大小可以確定,即大小是在編譯時期確定的,不必動態分配記憶體空間儲存虛擬函式表,所以不再堆中。

根據以上特徵,虛擬函式表類似於類中靜態成員變數。靜態成員變數也是全域性共用,大小確定。

所以我推測虛擬函式表和靜態成員變數一樣,存放在全域性資料區。其實,我們無需過分追究她位於哪裡,重點是:

- 她是編譯器在編譯時期為我們建立好的, 只存在一份;

- 定義類物件時, 編譯器自動將類物件的__vfptr指向這個虛擬函式表;

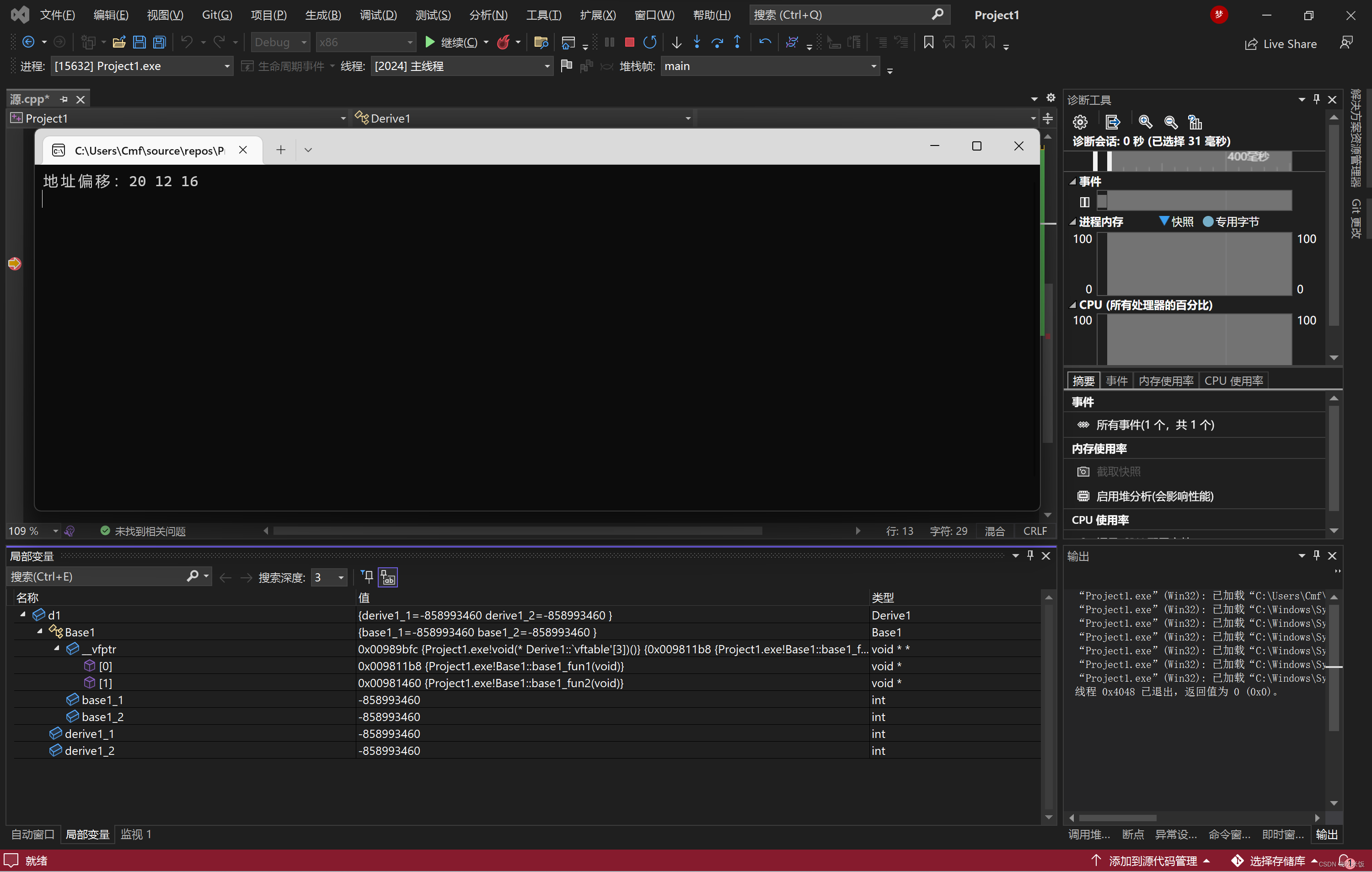

單繼承且本身不存在虛擬函式的繼承類的記憶體佈局

#include<iostream>

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

virtual void base1_fun2() {}

};

class Derive1 : public Base1

{

public:

int derive1_1;

int derive1_2;

};

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Derive1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_2) << std::endl;

Derive1 d1;

return 0;

}

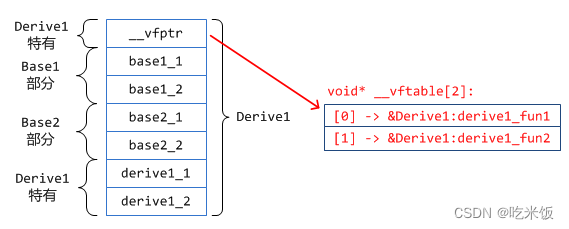

現在類的佈局情況應該是下面這樣:

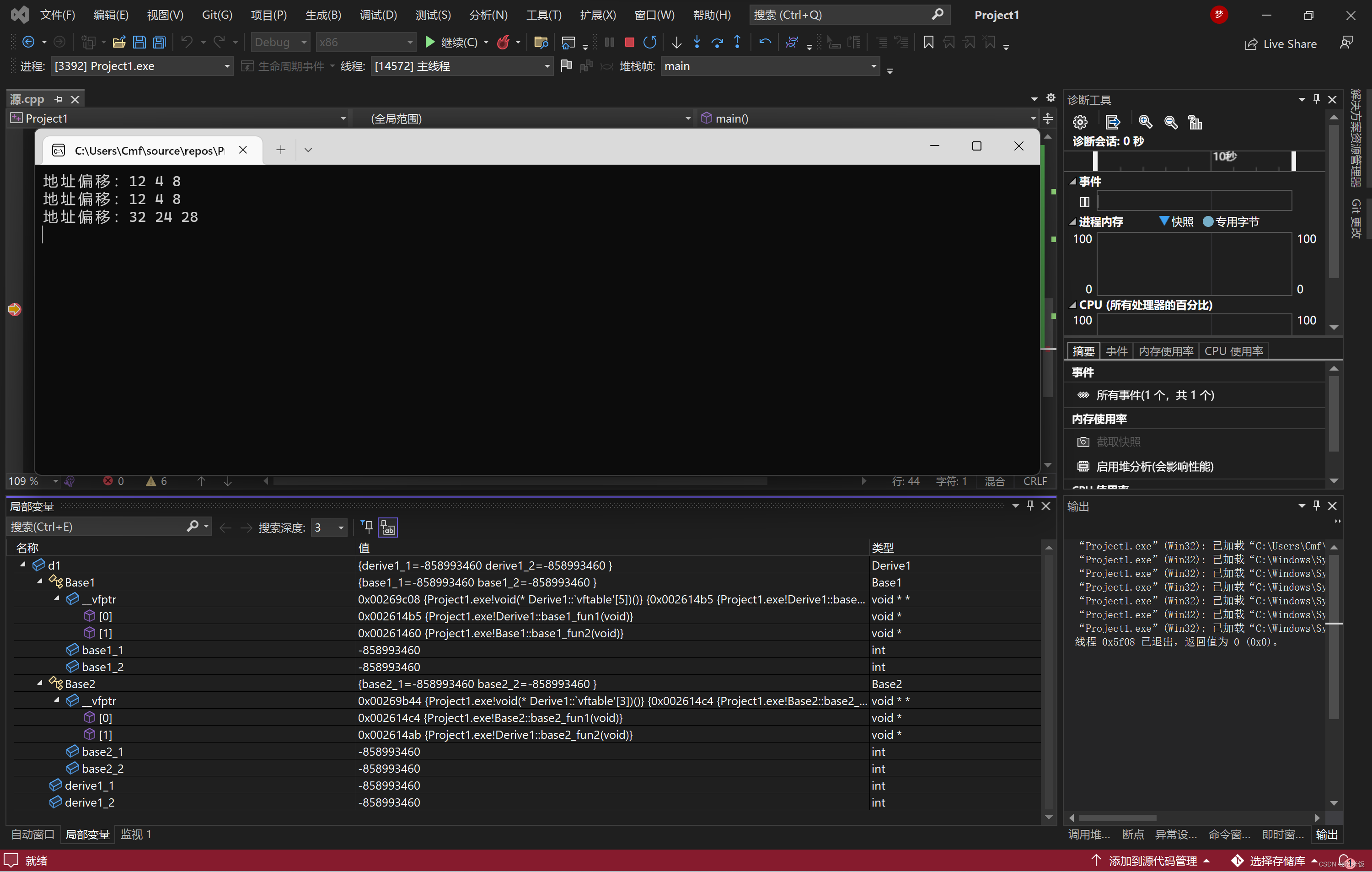

本身不存在虛擬函式(不嚴謹)但存在基礎類別虛擬函式覆蓋的單繼承類的記憶體佈局

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

virtual void base1_fun2() {}

};

class Derive1 : public Base1

{

public:

int derive1_1;

int derive1_2;

// 覆蓋基礎類別函數

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Derive1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_2) << std::endl;

Derive1 d1;

return 0;

}

特別注意那一行:原本是Base1::base1_fun1(),但由於繼承類重寫了基礎類別Base1的此方法,所以現在變成了Derive1::base1_fun1()!

那麼, 無論是通過Derive1的指標還是Base1的指標來呼叫此方法,呼叫的都將是被繼承類重寫後的那個方法(函數),多型發生了!!!

那麼新的佈局圖:

定義了基礎類別沒有的虛擬函式的單繼承的類物件佈局

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

virtual void base1_fun2() {}

};

class Derive1 : public Base1

{

public:

int derive1_1;

int derive1_2;

//和上上個類不同的是多了一個自身定義的虛擬函式. 和上個類不同的是沒有基礎類別虛擬函式的覆蓋.

virtual void derive1_fun1() {}

};

為嘛呢?現在繼承類明明定義了自身的虛擬函式,但不見了?類物件的大小,以及成員偏移情況居然沒有變化!

既然表面上沒辦法了, 我們就只能從組合入手了, 來看看呼叫derive1_fun1()時的程式碼:

Derive1 d1;

Derive1* pd1 = &d1;

pd1->derive1_fun1();

要注意:我為什麼使用指標的方式呼叫?說明一下:因為如果不使用指標呼叫,虛擬函式呼叫是不會發生動態繫結的哦!你若直接 d1.derive1_fun1();是不可能會發生動態繫結的,但如果使用指標:pd1->derive1_fun1(); 那麼 pd1就無從知道她所指向的物件到底是Derive1 還是繼承於Derive1的物件,雖然這裡我們並沒有物件繼承於Derive1,但是她不得不這樣做,畢竟繼承類不管你如何繼承,都不會影響到基礎類別,對吧?

pd1->derive1_fun1();

004A2233 mov eax,dword ptr [pd1]

004A2236 mov edx,dword ptr [eax]

004A2238 mov esi,esp

004A223A mov ecx,dword ptr [pd1]

004A223D mov eax,dword ptr [edx+8]

004A2240 call eax

組合程式碼解釋:

- 第2行:由於pd1是指向d1的指標,所以執行此句後 eax 就是d1的地址。

- 第3行:又因為Base1::__vfptr是Base1的第1個成員,同時也是Derive1的第1個成員,那麼: &__vfptr == &d1, clear?所以當執行完 mov edx, dword ptr[eax] 後,edx就得到了__vfptr的值,也就是虛擬函式表的地址。

- 第5行:由於是__thiscall呼叫,所以把this儲存到ecx中。

第6行:一定要注意到那個 edx+8,由於edx是虛擬函式表的地址,那麼 edx+8將是虛擬函式表的第3個元素,也就是__vftable[2]! - 第7行:呼叫虛擬函式。

結果:

- 現在我們應該知道內幕了!繼承類Derive1的虛擬函式表被加在基礎類別的後面!事實的確就是這樣!

- 由於Base1只知道自己的兩個虛擬函式索引 [0][1], 所以就算在後面加上了[2],Base1根本不知情,不會對她造成任何影響。

- 如果基礎類別沒有虛擬函式呢?

記憶體佈局

多繼承且存在虛擬函式覆蓋同時又存在自身定義的虛擬函式的類物件佈局

#include<iostream>

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

virtual void base1_fun2() {}

};

class Base2

{

public:

int base2_1;

int base2_2;

virtual void base2_fun1() {}

virtual void base2_fun2() {}

};

// 多繼承

class Derive1 : public Base1, public Base2

{

public:

int derive1_1;

int derive1_2;

// 基礎類別虛擬函式覆蓋

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

virtual void base2_fun2() {}

// 自身定義的虛擬函式

virtual void derive1_fun1() {}

virtual void derive1_fun2() {}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base2) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_1) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Derive1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_2) << std::endl;

Derive1 d1;

return 0;

}

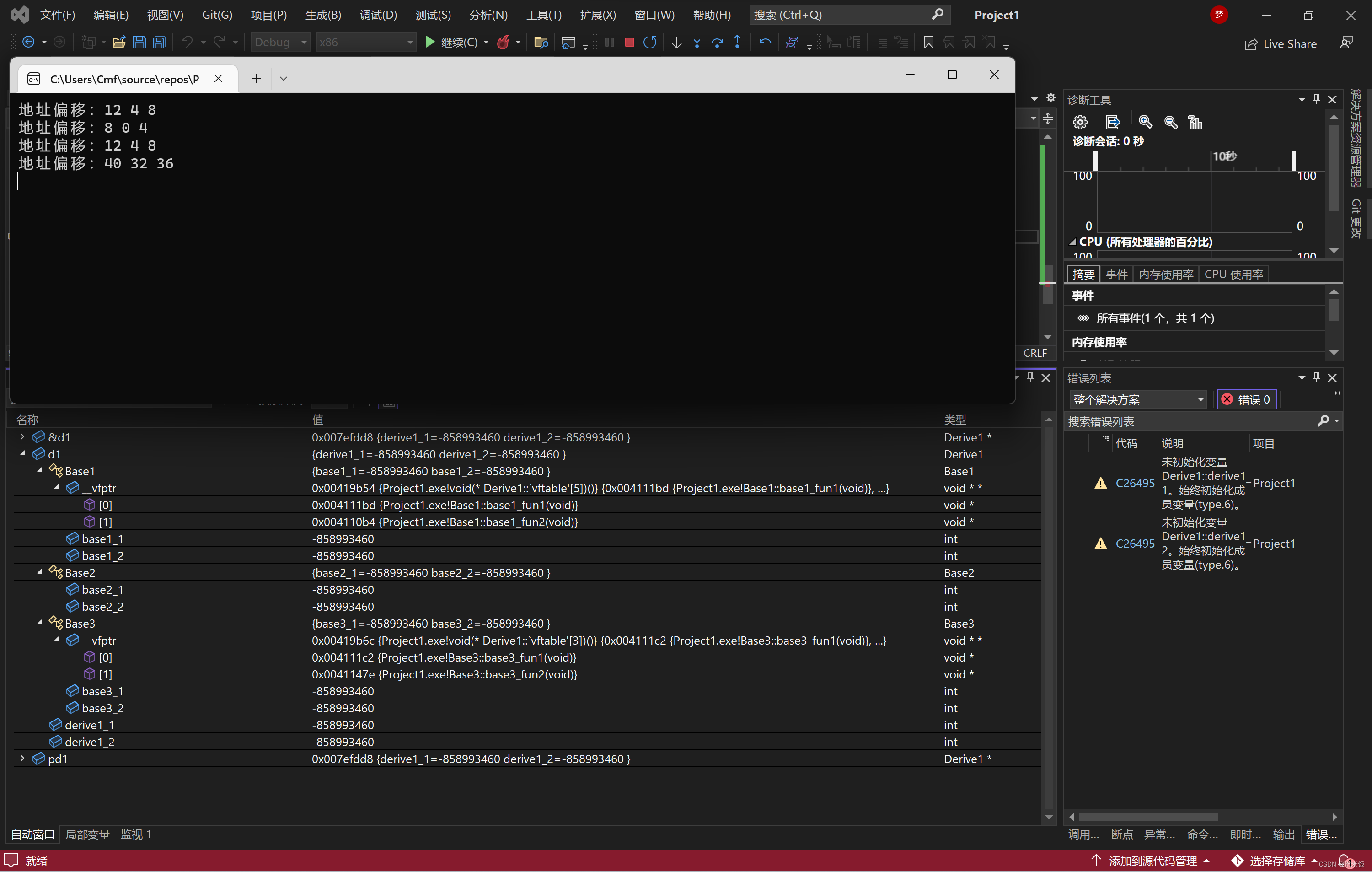

結論:

- 按照基礎類別的宣告順序,基礎類別的成員依次分佈在繼承中。

- 已經發生了虛擬函式覆蓋!

- 我們自己定義的虛擬函式呢?怎麼還是看不見?

繼承反組合,這次的呼叫程式碼如下:

Derive1 d1;

Derive1* pd1 = &d1;

pd1->derive1_fun2();

反組合程式碼如下:

pd1->derive1_fun2();

0008631E mov eax,dword ptr [pd1]

00086321 mov edx,dword ptr [eax]

00086323 mov esi,esp

00086325 mov ecx,dword ptr [pd1]

00086328 mov eax,dword ptr [edx+0Ch]

0008632B call eax

解釋:

- 第2行: 取d1的地址

- 第3行: 取Base1::__vfptr的值

- 第6行: 0x0C, 也就是第4個元素(下標為[3])

結論:Derive1的虛擬函式表依然是儲存到第1個擁有虛擬函式表的那個基礎類別的後面的.

類物件佈局圖:

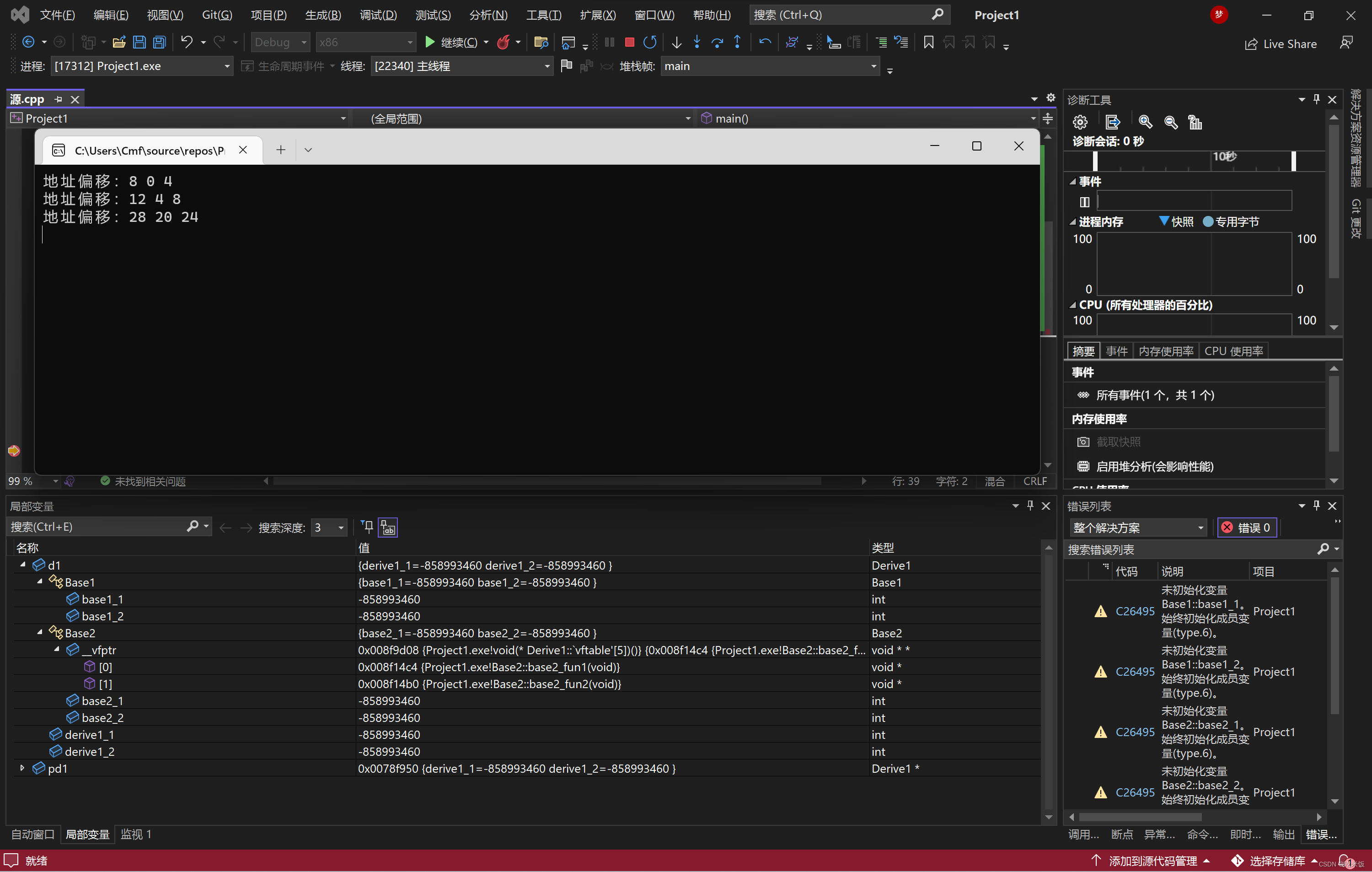

如果第1個直接基礎類別沒有虛擬函式(表)

#include<iostream>

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

};

class Base2

{

public:

int base2_1;

int base2_2;

virtual void base2_fun1() {}

virtual void base2_fun2() {}

};

// 多繼承

class Derive1 : public Base1, public Base2

{

public:

int derive1_1;

int derive1_2;

// 自身定義的虛擬函式

virtual void derive1_fun1() {}

virtual void derive1_fun2() {}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base2) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_1) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Derive1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_2) << std::endl;

Derive1 d1;

Derive1* pd1 = &d1;

pd1->derive1_fun2();

return 0;

}

Base1已經沒有虛擬函式表了嗎?重點是看虛擬函式的位置,進入函數呼叫(和前一次是一樣的):

Derive1 d1;

Derive1* pd1 = &d1;

pd1->derive1_fun2();

反組合呼叫程式碼:

pd1->derive1_fun2();

008F667E mov eax,dword ptr [pd1]

008F6681 mov edx,dword ptr [eax]

008F6683 mov esi,esp

008F6685 mov ecx,dword ptr [pd1]

008F6688 mov eax,dword ptr [edx+0Ch]

008F668B call eax

這段組合程式碼和前面一個完全一樣,那麼問題就來了,Base1 已經沒有虛擬函式表了,為什麼還是把Base1的第1個元素當作__vfptr呢?

不難猜測: 當前的佈局已經發生了變化, 有虛擬函式表的基礎類別放在物件記憶體前面?不過事實是否屬實?需要仔細斟酌。

我們可以通過對基礎類別成員變數求偏移來觀察:

所以不難驗證: 我們前面的推斷是正確的, 誰有虛擬函式表, 誰就放在前面!

現在類的佈局情況:

兩個基礎類別都沒有虛擬函式表

#include<iostream>

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

};

class Base2

{

public:

int base2_1;

int base2_2;

};

// 多繼承

class Derive1 : public Base1, public Base2

{

public:

int derive1_1;

int derive1_2;

// 自身定義的虛擬函式

virtual void derive1_fun1() {}

virtual void derive1_fun2() {}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base2) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_1) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Derive1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_2) << std::endl;

Derive1 d1;

Derive1* pd1 = &d1;

pd1->derive1_fun2();

return 0;

}

可以看到, 現在__vfptr已經獨立出來了, 不再屬於Base1和Base2!

再看看偏移:

&d1==&d1.__vfptr 說明虛擬函式始終在最前面!

記憶體佈局:

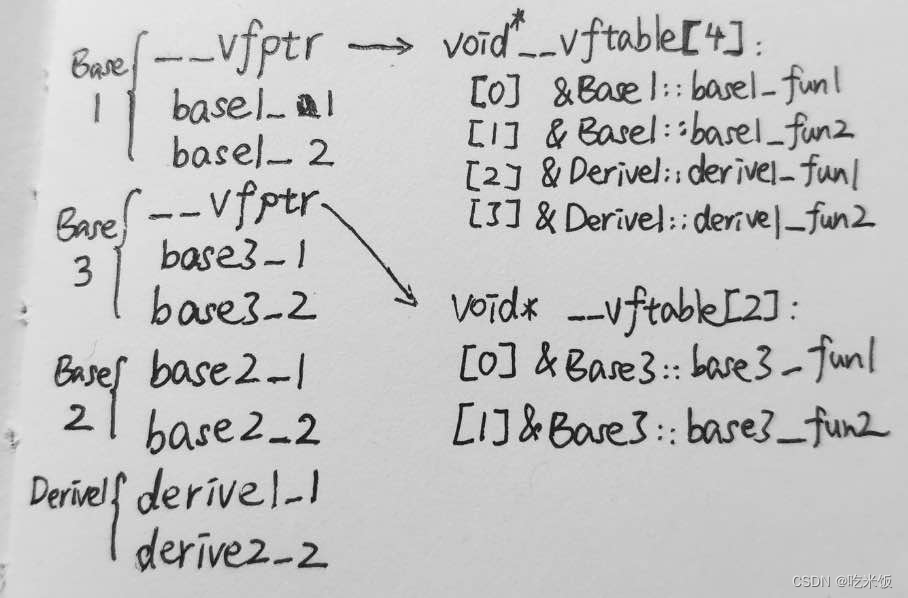

如果有三個基礎類別: 虛擬函式表分別是有,沒有,有!

#include<iostream>

class Base1

{

public:

int base1_1;

int base1_2;

virtual void base1_fun1() {}

virtual void base1_fun2() {}

};

class Base2

{

public:

int base2_1;

int base2_2;

};

class Base3

{

public:

int base3_1;

int base3_2;

virtual void base3_fun1() {}

virtual void base3_fun2() {}

};

// 多繼承

class Derive1 : public Base1, public Base2, public Base3

{

public:

int derive1_1;

int derive1_2;

// 自身定義的虛擬函式

virtual void derive1_fun1() {}

virtual void derive1_fun2() {}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_1) << " " << offsetof(Base1, base1_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base2) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_1) << " " << offsetof(Base2, base2_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Base3) << " " << offsetof(Base3, base3_1) << " " << offsetof(Base3, base3_2) << std::endl;

std::cout << "地址偏移:" << sizeof(Derive1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_1) << " " << offsetof(Derive1, derive1_2) << std::endl;

Derive1 d1;

Derive1* pd1 = &d1;

pd1->derive1_fun2();

return 0;

}

記憶體佈局:

只需知道: 誰有虛擬函式表, 誰就往前靠!